Jay Fisher - Fine Custom Knives

New to the website? Start Here

"Raptor"

My client requested a pair of custom knives, juxtaposed, based on my "Malaka" knife pattern design. He graciously trusted me with the simple outline of the idea, which is what all artists desire and are thankful for. I based my sculptural creations on the gemstones used in the handles, each intensely old and unique in their own ways.

In the beginning of one of the earliest time periods on our planet, the Proterozoic, there was little oxygen on our planet. Proterozoic is the combination of two Greek words meaning "earlier life." This eon began 2.5 billion years ago. It's overwhelming to consider this great age; our short time on this planet is simply a wisp of smoke in a truly ancient and ongoing bonfire. During this time, ancient shallow seas were filled with iron; our planet was a true red world.

Along came the first major life form, cyanobacteria. These organisms produced oxygen as a byproduct of photosynthesis, and created the very oxygen we live and breathe today. They were so widespread that in the billions of years they thrived, that they changed our very planet's atmosphere. I can imagine being there then, in a scary, volcanic boiling world with shallow red seas, a lack of oxygen, and giant mats of bacteria bubbling up through the thick, metal and mineral-soaked water.

As time passed, these bacterial colonies were buried by cataclysmic events, by normal sedimentary actions, and they were preserved in the sand, mud, and muck below the seas. Their biological compounds were slowly dissolved, leaving voids that were slowly, eternally filled in by minerals carried from the water above. These minerals hardened, solidified and were held in great pressure and time until they were solid rock.

Because the seas contained such high amounts of iron, the fossils of these colonies became iron-based minerals, and the incredibly large mass of them became an entire range of mountains, high in iron. Today, we call this the Proterozoic Biwabik Iron Formation, in the Mesabi iron range of northern Minnesota.

To give you an idea of size, this range is 110 miles long with the iron mineral taconite over three miles thick. Taconite is what remains of the great Proterozoic seas and the stromatolites, containing 15% iron and quartz, chert, and carbonate. Extensive iron mining was supported by mining the low-grade iron ore taconite; it was blasted, crushed, separated with magnets, and rolled to make pellets that were then further processed to make iron. These created many iron and steel products we use today.

In this iron formation, some very special stromatolite fossils originate. They are rich in iron-red color, with inclusions of silvery-gray hematite (iron oxide) and chert, quartz and carbonates. The pit where these are found is called the "Mary Ellen" pit, in the Mesabi Range in St. Louis county in Minnesota.

The name Mesabi is an Ojibwa Indian word meaning "giant," and this is because it's the largest of the four major iron ranges in the region. Giant, indeed, is the legacy of the stromatolite.

In this duplex art piece, the Mesabi knife and sculpture exhibit the nature of the stromatolite, fossilized and preserved in the beautiful handle of rich, deep reds. In the handle, you can see the amazing details of this once living fossil, beautiful and intricate and mind-numbingly old.

In Mesabi, the red Fossilized Stromatolite chert gemstone exhibits a curvaceous, flowing life form, and I interpreted this into the artistic forms of the piece. The closest artistic style would be art nouveau. I chose a flowing vine filework for the blade, I engraved an interlocking, organic pattern for the bolsters, I sculpted a matching pattern of curves, ebbs and tides in the bronze. I employed a rich red patina on the bronze fading to coppery highlights. The patina was accomplished with selective heating and potassium sulfate, ferric nitrate, and iron oxide. I polished a curved face of the raw gemstone and attached it to the nameplate to illustrate what mystery and beauty exists in the jagged, rough chert rock. I engraved the name and the age of the stone on the nameplate. It still awes me to read it: 2300 million years ago... unbelievable, incredible, astounding.

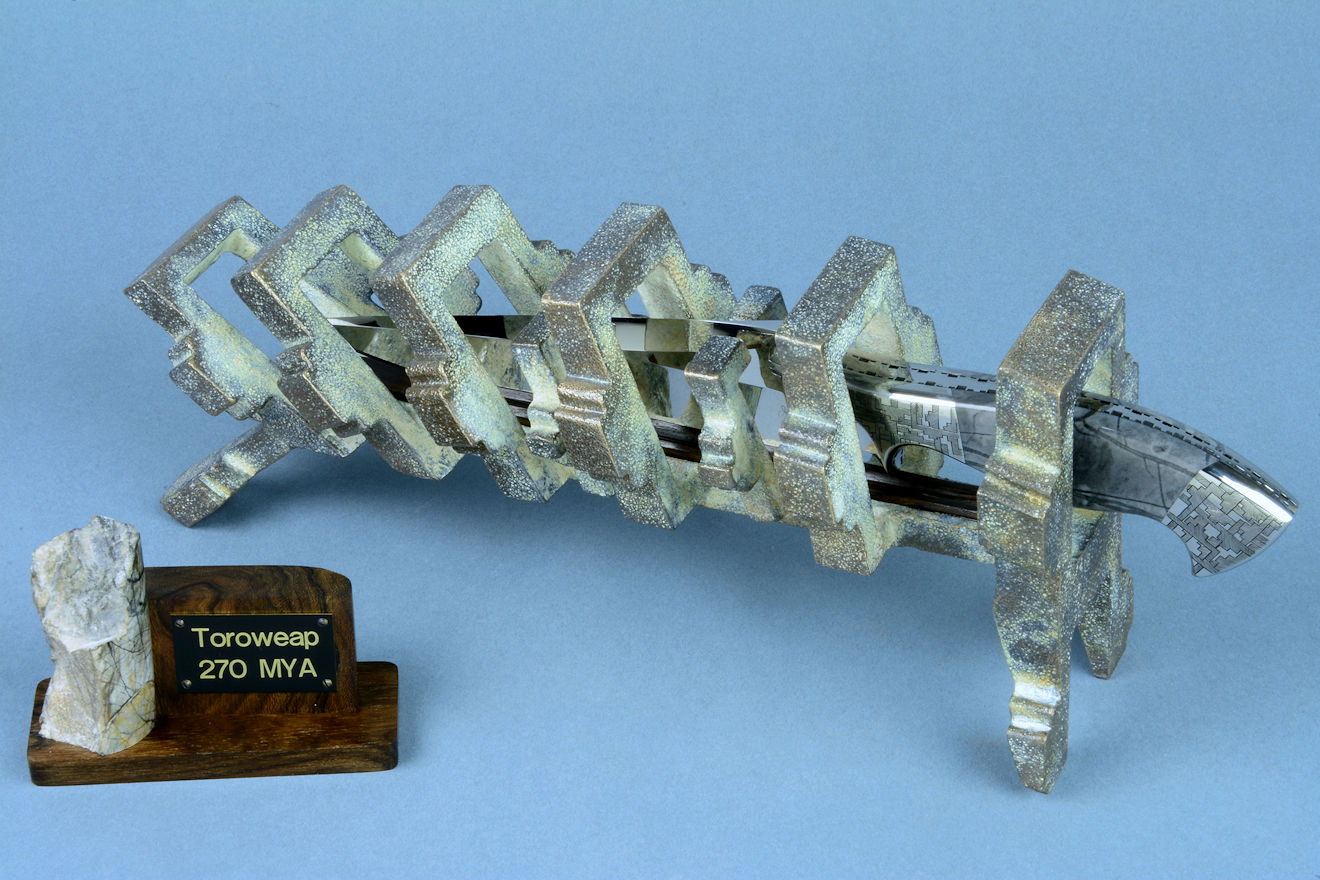

Like Mesabi, Toroweap is based in the ancient past. The word Toroweap is a Paiute Indian word meaning dry, barren valley. The Toroweap formation is 275 million years old and 250 feet thick, and can be seen in the face of the Grand Canyon.

270 million years ago, western Utah was under water. The sea grew and shrank, the shore moved and retreated, leaving many tide pools. At the bottom of these were the remains of animals, sediment, mud, clay, dolomite, and sand. This rested on the Kaibab limestone, and was eventually solidified into a mass. That mass was compressed and formed into limestone itself. This mass was folded into the earth in the Sevier orogeny. This impressive geological act of subduction forced the limestone deep into areas of high pressure and heat, and volcanism added silver sulfide and other minerals into the mass. A hundred million years after the formation, even more metamorphic heat was generated, converting the limestone to marble. The limestone had been fractured, re-formed, filled and compressed, creating the fascinating structure of the Picasso Marble on "Toroweap."

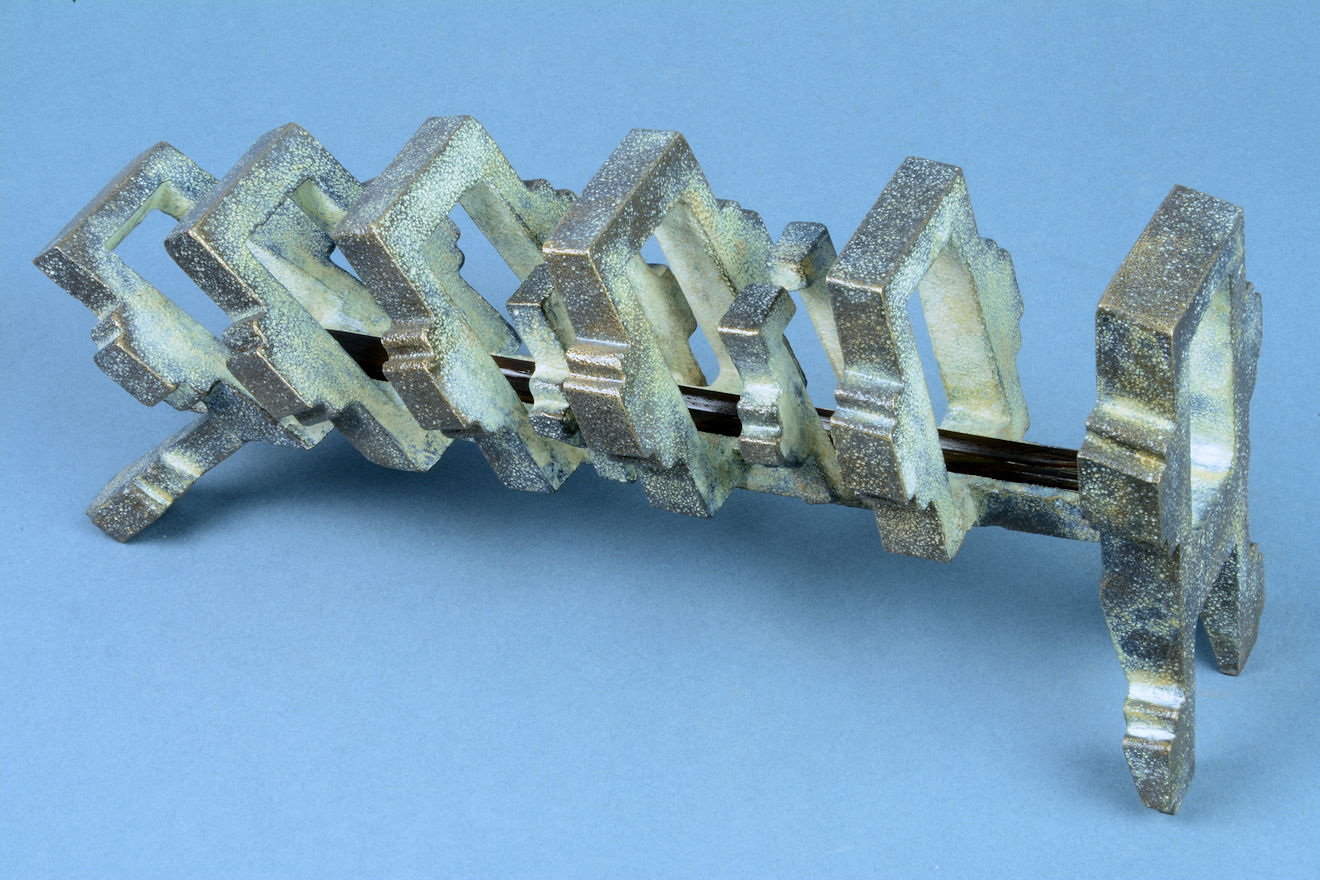

Like Mesabi, the Toroweap formation was formed in an incredibly ancient, shallow sea filled with living things. Though there are no obvious life form fossils visible to the naked eye, other tremendous forces are on display in the stone. The fracturing, reforming, breaking, filling, and transformation exhibit an almost mechanical appearance to the rock. This was my inspiration for Toroweap.

The Picasso Marble displays hard angles, straight and geometric forms, gentle changes in tone in distinctive grays and hints of gold. The closest artistic style would be art deco, with almost an architectural regularity of hard-angled shapes. I followed this design idea into the geometric squared forms of the filework, and displayed it in the hand-engraving of the bolsters, and blossomed the form in the bronze sculpture. Even the very complex patina of the bronze with grays, whites, and golds follows the form and idea. The patina was accomplished with potassium sulfate, bismuth nitrate, and titanium dioxide. I included a polished gemstone on the nameplate with rough, cleaved surface for contrast. The nameplate details the intense age of the rock, 270 million years ago. It's just astounding to think that was was once mud and remains of tidal pools was forced into beautiful gem.

The knives blades are made of 440C high chromium martensitic stainless steel, hardened, triple-tempered, and cryogenically treated with my deep cryogenic process, creating fine grained, extremely beautiful blades that will last indefinitely. Though these are works of art, they are true extreme cutting instruments, treated and finished to their highest potential. The tangs are fully tapered, and the knives are well-balanced and substantial.

While they rest in their sculpted bronze forms, they resemble the skeletons of some ancient life form, long ago forgotten to time.

For the bronzes, I sculpted the forms in wax, and I cast them with a lost wax process, and there was no mold. They are truly one-of-a-kind. The silicon bronze is very heavy and solid, the castings are thick and robust and took quite a bit of work and time to create. The finishing, texturing, and patina is complex on both sculptures, making them both unique art works of their own and stunning in contrast. The knives slip into the sculptures and rest on a ziricote hardwood slide. Ziricote hardwood is also used on the nameplates, with engraved black brass.

Even without the knives, the bronze sculptures are works of art on their own.

Like Toroweap, the Mesabi sculpture is a unique form.

I truly enjoyed creating this entire piece. The exemplary form of the knife, the materials and treatment, the embellishment and casting: this is the reason I love knives. It's an honor to create these unique pieces for others who love knives, too.

Thanks most to H. L. for his patronage!

Jay,

I hope you never get tired of all the superlatives your customers and collectors heap upon your

work-they are all well-deserved in my experience! I have spent literally hours looking at the photos

you provided, and I had become progressively more excited about seeing the actual knives and

presentation displays the longer I studied them. I appreciate the exposition with the photos which

details the time periods leading to the formation of the gemstone in the handles; that provided

context for the knife names and got me to thinking about how the sculptures “hit” me. I suppose,

like any works of art, everyone will see something different in these sculptures. For me, the Mesabi

sculpture brings to mind the fire prevalent in a cooling earth, and the Toroweap sculpture captures

the solidity of the stone after thousands of years of compression.

The knives and sculptures arrived today. Thank you for getting them here so quickly. Your pictures are wonderful, but having the knives and sculptures in my home gives me a much better appreciation for the master craft which you have created. I love the way the engravings on the knives reflect the sculptures, and the finish on the blades and handles is flawless. I can’t imagine how you achieve that.

You have made me something which I will treasure, and which I expect my children will treasure long after I’m gone. My thanks are far too little as recompense for the effort you have made on my behalf, but you have them nonetheless. Thank you for bringing to life the vague notion of juxtaposition I had when we first discussed this project in such a novel and artistic way.

--H.

| Main | Purchase | Tactical | Specific Types | Technical | More |

| Home Page | Where's My Knife, Jay? | Current Tactical Knives for Sale | The Awe of the Blade | Knife Patterns | My Photography |

| Website Overview | Current Knives for Sale | Tactical, Combat Knife Portal | Museum Pieces | Knife Pattern Alphabetic List | Photographic Services |

| My Mission | Current Tactical Knives for Sale | All Tactical, Combat Knives | Investment, Collector's Knives | Copyright and Knives | Photographic Images |

| The Finest Knives and You | Current Chef's Knives for Sale | Counterterrorism Knives | Daggers | Knife Anatomy | |

| Featured Knives: Page One | Pre-Order Knives in Progress | Professional, Military Commemoratives | Swords | Custom Knives | |

| Featured Knives: Page Two | USAF Pararescue Knives | Folding Knives | Modern Knifemaking Technology | My Writing | |

| Featured Knives: Page Three | My Knife Prices | USAF Pararescue "PJ- Light" | Chef's Knives | Factory vs. Handmade Knives | First Novel |

| Featured Knives: Older/Early | How To Order | 27th Air Force Special Operations | Food Safety, Kitchen, Chef's Knives | Six Distinctions of Fine Knives | Second Novel |

| Email Jay Fisher | Purchase Finished Knives | Khukris: Combat, Survival, Art | Hunting Knives | Knife Styles | Knife Book |

| Contact, Locate Jay Fisher | Order Custom Knives | Serrations | Working Knives | Jay's Internet Stats | |

| FAQs | Knife Sales Policy | Grip Styles, Hand Sizing | Khukris | The 3000th Term | Videos |

| Current, Recent Works, Events | Bank Transfers | Concealed Carry and Knives | Skeletonized Knives | Best Knife Information and Learning About Knives | |

| Client's News and Info | Custom Knife Design Fee | Military Knife Care | Serrations | Cities of the Knife | Links |

| Who Is Jay Fisher? | Delivery Times | The Best Combat Locking Sheath | Knife Sheaths | Knife Maker's Marks | |

| Testimonials, Letters and Emails | My Shipping Method | Knife Stands and Cases | How to Care for Custom Knives | Site Table of Contents | |

| Top 22 Reasons to Buy | Business of Knifemaking | Tactical Knife Sheath Accessories | Handles, Bolsters, Guards | Knife Making Instruction | |

| My Knifemaking History | Professional Knife Consultant | Loops, Plates, Straps | Knife Handles: Gemstone | Larger Monitors and Knife Photos | |

| What I Do And Don't Do | Belt Loop Extenders-UBLX, EXBLX | Gemstone Alphabetic List | New Materials | ||

| CD ROM Archive | Independent Lamp Accessory-LIMA | Knife Handles: Woods | Knife Shop/Studio, Page 1 | ||

| Publications, Publicity | Universal Main Lamp Holder-HULA | Knife Handles: Horn, Bone, Ivory | Knife Shop/Studio, Page 2 | ||

| My Curriculum Vitae | Sternum Harness | Knife Handles: Manmade Materials | |||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 1 | Blades and Steels | Sharpeners, Lanyards | Knife Embellishment | ||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 2 | Blades | Bags, Cases, Duffles, Gear | |||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 3 | Knife Blade Testing | Modular Sheath Systems | |||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 4 | 440C: A Love/Hate Affair | PSD Principle Security Detail Sheaths | |||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 5 | ATS-34: Chrome/Moly Tough | ||||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 6 | D2: Wear Resistance King | ||||

| Funny Letters and Emails, Pg. 7 | O1: Oil Hardened Blued Beauty | ||||

| The Curious Case of the "Sandia" |

Elasticity, Stiffness, Stress, and Strain in Knife Blades |

||||

| The Sword, the Veil, the Legend |

Heat Treating and Cryogenic Processing of Knife Blade Steels |